63 days in the Indian Ocean

I photographed the Sydney to Hobart yacht Race in 1998. The storm that exploded on the fleet, referred to as the “Bass Strait Bomb”, rolled several boats more than once. Storm winds of up to 80 knots sank 5 boats, forced 7 to be abandoned, 16 to call for help and 115 boats to retire.

During that event 56 crew were rescued and 6 men were lost to the sea. It was the worst tragedy in the history of the Sydney to Hobart Yacht Race.

My pilot, Ralph Schwertner, my 21 year–old daughter Alice (also a photographer), and I, stayed out in the storm in our plane. We assisted search and rescue efforts to locate the stricken vessels. It was a truly traumatic experience.

After that race I became fascinated with understanding what drew men to ocean racing. I wanted to understand the experience of being at sea. I had always had a boat and enjoyed sailing, but I hadn’t experienced true ocean sailing.

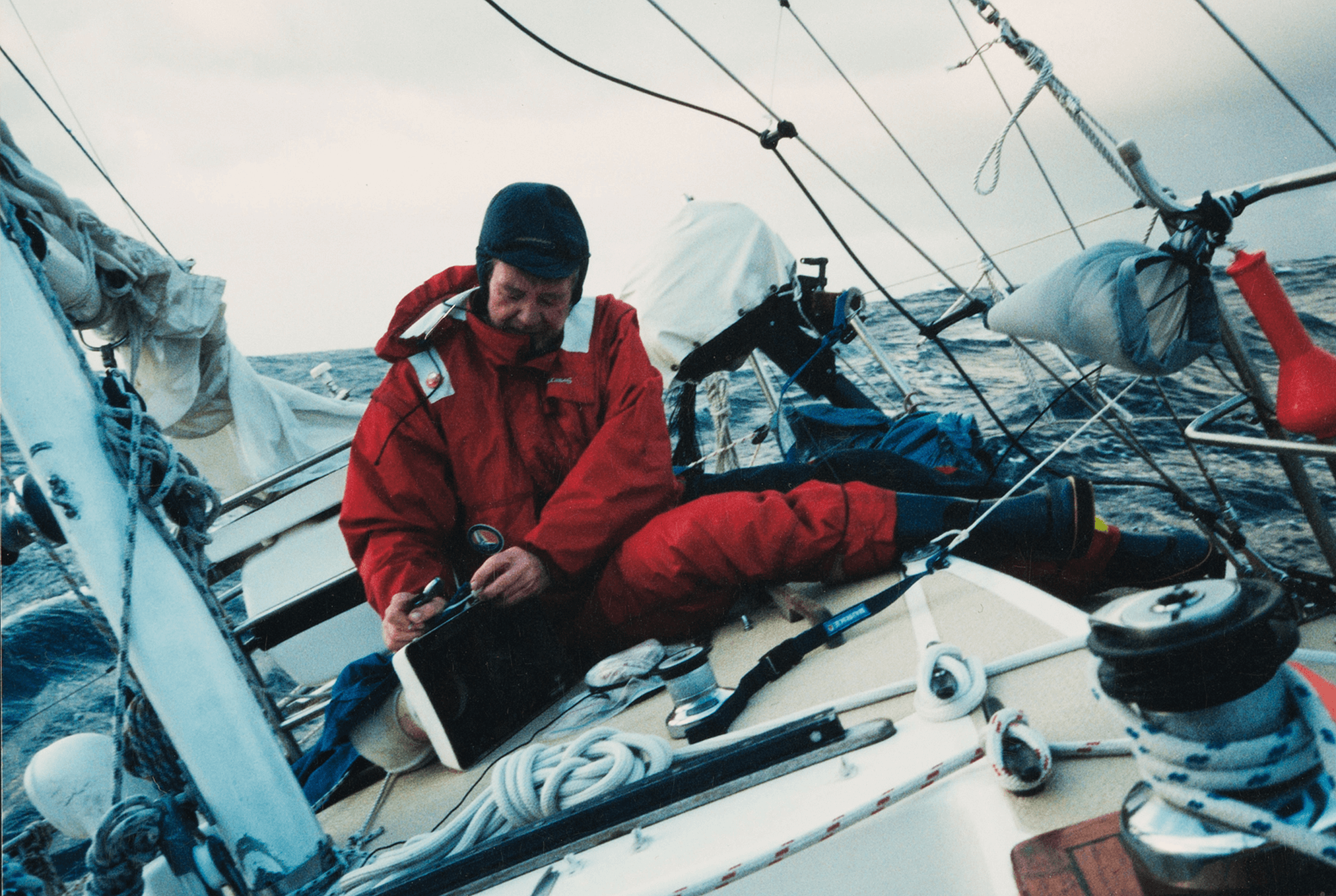

I gained my pilots license to help me better understand the aircraft that I was photographing from. I wanted to understand the aeronautical procedures and the aircrafts capabilities so that I was talking the same language as my pilot. Then together we could position the plane where I wanted to be to capture the images of the yachts. Similarly, I thought it would make me a better yacht race photographer to sail a long ocean passage.

In October 2000 I was offered that opportunity. I was invited to cross the Indian Ocean from Cape Town South Africa, to Freemantle Australia via St Paul Island, which sits on the cusp of the Southern Ocean. The Indian Ocean is the third largest of the worlds oceanic divisions, covering approximately 20% of the water on the Earths surface (globalcitymap.com).

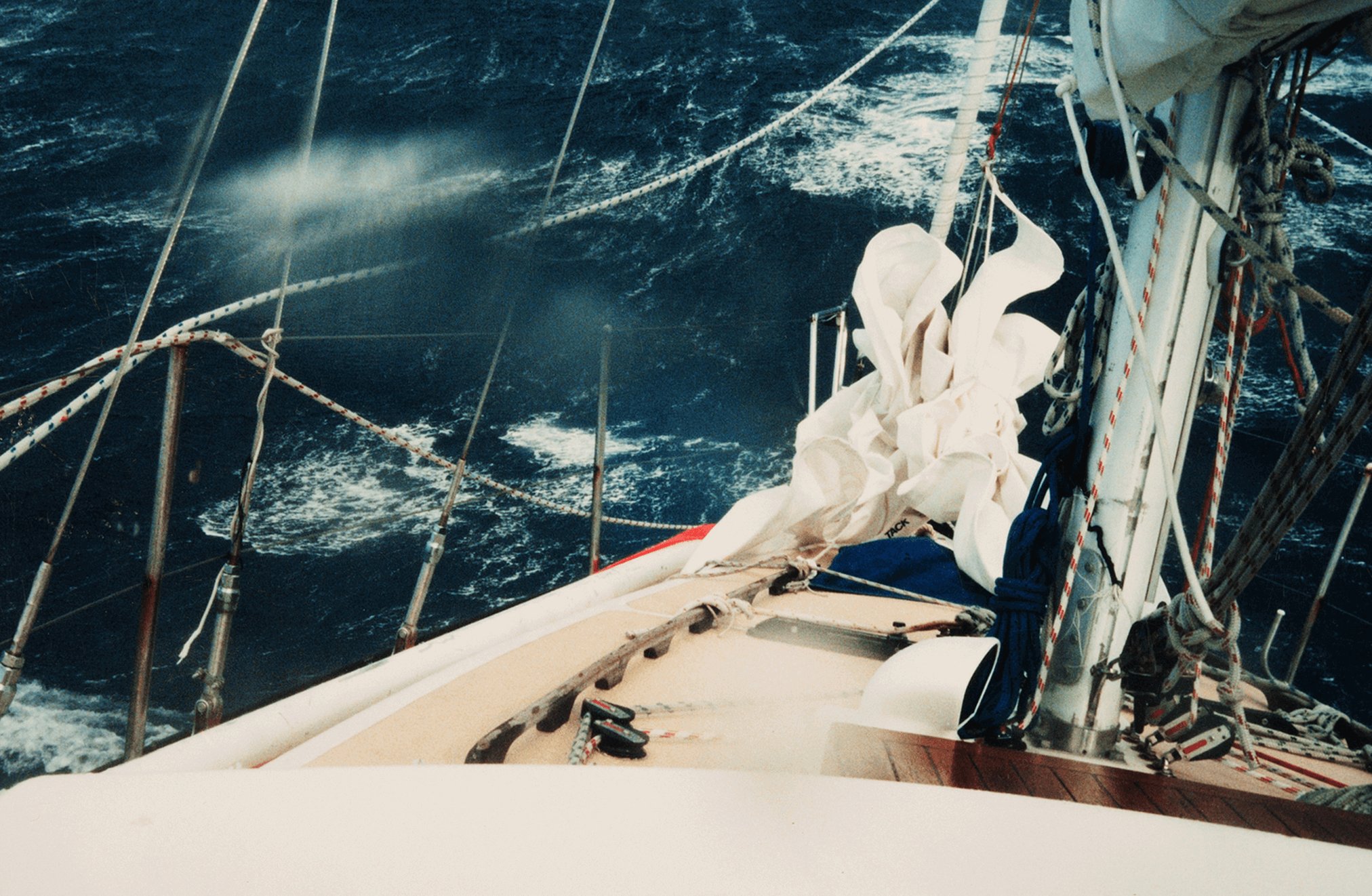

It is a serious voyage. Our little ship was to be the 35–foot Martzcraft yacht Avalon of Tasman. There would be just three of us aboard – the skipper, 77 year–old retired Doctor Joe Cannon, 63 year–old retired businessman John Wedd and myself. It was to be the most life–threatening experience of my life. I experienced exactly what I saw from the Aero Commander aircraft in 1998. But this storm lasted for 14 days. This is the story.

June 7, 2001

A storm has been raging most of the night. We are 550 nautical miles west of St Paul Island in the Indian Ocean running under a storm jib. The wind is 60 knots plus from the North West. To put this in perspective, a hurricane is classified by winds greater than 64 knots. We’re approximately half way between South Africa and Australia. St Paul Island is to be the first land we have seen in a month. The barometer has dropped to 1004.

(A barometer measures air pressure. Imbalances in air pressure cause wind and weather. So changes in air pressure are important to follow when you’re at sea. Low pressure 980 – 1000 means stormy weather. High pressure 1020 – 1030 means dry weather. If the pressure is changing rapidly, this generally suggests that strong winds are coming. http://www.bethandevans.com/pdf/baro.pdf)

We are lying a hull (the boat’s broad side to the wind), riding out a howling storm. I am sitting in the cockpit under the dodger, the canvas canopy that covers you at the wheel for protection. I’m on watch sailing the boat while Joe and John get some rest. Occasionally a massive wave breaks right over the boat.

I have rediscovered crunchy peanut butter after 30 years! I have been spreading it on biscuits and munching it down followed by Kalamata olives and Parmesan cheese. It’s quick and easy.

As the day progressed the wind dropped as we reached the centre of the low. We are looking forward to a clearing southerly and hopefully a high pressure system following it. Better weather ahead.

The Southerly came through during the night stronger than we expected. Then an amazing thing happened. The barometer rose from 1010 to 1024 in less than three hours. This heralded two weeks of the worst weather that I could have imagined.

June 8

The sky to the south is streaked with long storm clouds. By midday the wind is blowing with a vengeance. 60 knots again. We settle down to ride out the storm, which has already delayed our arrival at St Paul by two days.

June 9

After 60 hours the storm is abating and the sea is beginning to go down. We have been blown 100 miles north of our course. We will need northerly winds soon to enable us to progress south. If this doesn’t happen we will lose our opportunity to visit St. Paul.

June 11

Our 30th day at sea. The little ship has coped well with a month at sea although it is now damp down below. A beautiful morning but the barometer is low – 1002. It seems strange to have such a beautiful morning with a very low glass (barometer reading). Particularly when we have just had the worst weather with a very high glass. It seems back to front to me. Ominous.

June 12

0130 hours (1.30am). John is on watch. We’ve had a knock down. The wind is extreme again. The waves are massive and rolling. Keeping the little boat upright with her stern to the swell is a mammoth task. It’s incredible that this is the first time she has been put on her side. John is drenched.

There is no heating on the boat and we have limited clothing. Staying dry is an essential part of survival.

0200 (2am). I relieve John.

Woken 20 minutes before, I put on my 5 layers of wet weather gear and take a briefing. Then the storm boards go in (shutting the cabin off from the weather outside) and I’m on my own in the dark.

This is the worst watch. From 2–4am your body is at its lowest ebb. You’re standing in water up to your calves. Cold salt water sprays the boat constantly. My job for the next two hours is to keep the boat positioned in such a way that she surfs down the waves, never letting her side parallel to the walls of water.

The waves are like mountains rolling in behind you. The stern light lets you see the wave building 1–2 minutes away and you position the boat accordingly. Being hit by one of these on our side would engulf the boat and possibly dismast us.

Sometimes 2 hours feels like a long time, but you are never bored.

I stay on watch until 4am, keeping our stern into the breaking seas.

0415 (4.14am). Joe is on watch. I’m down below. Exhausted. I’ve wedged myself into my bunk. My bag is jammed down one side of me and sail bags are on the other to stop me rolling out of my bunk. The seas are huge. The bunks are right along the inside of the hull. Every wave that hits the side of the boat is like being hit by a sledgehammer. Joe described it as being like parking a car in an intersection, going to sleep in the back seat and then being hit side on by another car – over and over again.

I fastened the lea cloth (the canvas that stops you falling out of your bunk) and fell quickly into an uneasy sleep.

Seconds later I was upended. Thrown across the cabin. I tore through the lea cloth and fell 2–3 meters onto a hard surface. There are things falling onto me from all above. There is water everywhere. Water is pouring into the cabin. It’s pitch dark. Shocked, I fumbled about for a light but nothing was where it should be. Strangely, there was no sound. I couldn’t hear Joe. I couldn’t hear John. After the relentless howling of the storm winds it is totally disorienting to be in silence. The noise of the wind and sea was gone. For a minute and a half I tried to make sense of the chaos. After a month aboard I knew the inside of the boat intimately, but I couldn’t recognize a thing. Then I realized we were upside down. Capsized. I was lying in the roof.

As suddenly as she had gone over, the boat righted herself. I found a light. The cabin was a shambles. The carpet and inspection hatches were on the leeward bunk. The starboard lockers were empty. The crockery was in the bilge.

John went on deck to find the skipper. I found my camera and took a photo.

When we rolled Joe hit the wheel, then a winch and then the dodger. He went under the boat into the ocean. Then his Stormy Seas jacket inflated as it is supposed to do when you are submerged, and he shot to the surface – only the boat was above him. His head hit the bottom of the cockpit. When the boat righted herself Joe was on his head in a cockpit full of water with several cracked ribs.

The dodger, our protection from the weather at the helm, had been swept away. Half the cabin ventilators, that let air into the cabin without water, were gone. Two torches were gone. The chain from the chain locker fell out and it is over the side. The HF radio is wet. Our means for communicating is gone.

We got the Skipper down below. He was wet through. Our top priority was to get him dry and into his bunk. We managed to find some dry thermals and sails. We made a nest in his bunk, packing the sails around him to make him immobile. The extent of his injuries rendered him temporarily out of action.

John and I took shifts. Two hours on, two hours off for the next twenty–four hours.

June 13

There is still a big leftover sea but we’ve cleaned up the boat and we’re underway by 0700 (7am). The radio is history. Stopping at St Paul Island is no longer an option. We must head for Freemantle (Perth) because our families will hear no further word until we arrive.

Everything is so wet. The most fundamental thing on a voyage like this is to keep dry. Our dry space was gone. The bedding was wet, clothes, seats, the labels were off the cans. Even the mugs in their racks were full of water.

I made a beef satay for dinner and we decide to have a bottle from the near empty wine supply to celebrate our recovery.

June 14

Our celebration was short lived.

0200 (2am) The wind has strengthened again. Barometer 1001.

0900 (9am) The wind has suddenly increased to storm force. The seas are huge. We started the motor and managed to get our bow into the wind as huge waves break over us. We put out the sea anchor and the little boat stabilized. Thank heavens.

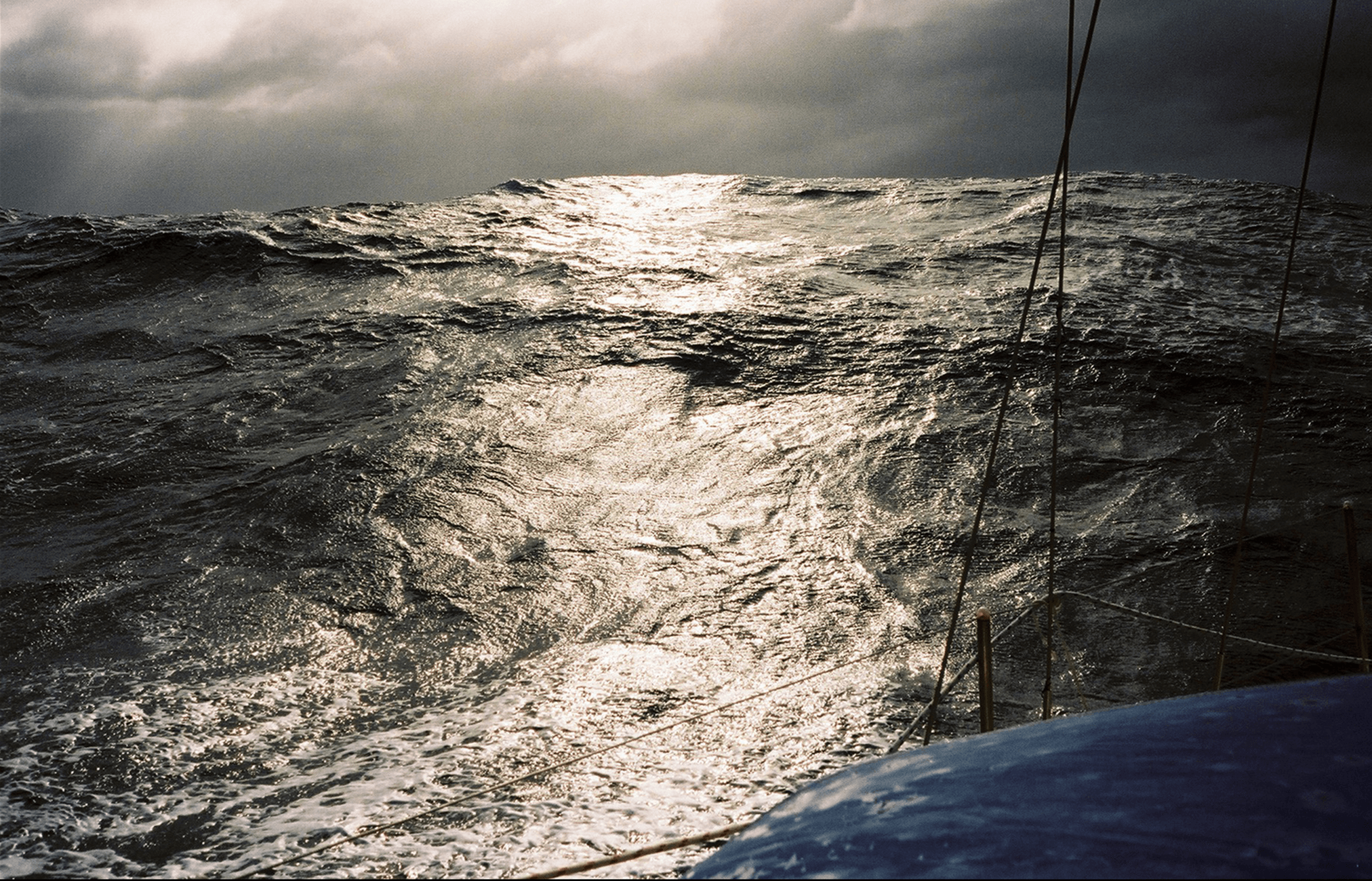

The sea looks like the ‘98 Sydney – Hobart storm. It is dangerous. Joe estimates the sea to be 15 meters with 70 knots of wind (140km/hour). It is a cyclone.

June 15

It is uncomfortable hanging on to the sea anchor but it may well have saved the little ship yesterday. It also allowed John and I to sleep for 6 hours. We are exhausted. Our decision to get underway again was made for us when the cable on the sea anchor chafed through. At least it provided some relief.

The little ship seems happier now that we are underway again. Me too. I want to get away from this part of the ocean, which has produced three terrible storms one after the other.

June 16

0200 (2am) Another storm. I can’t believe it. The boat is overpowered by the storm jib. We have taken it off.

0600 (6am) The wind strength and sea state are beyond my experience. Awesome and frightening.

2030 (8.30pm) We are lying ahull again (our broad side to the wind). The ocean is flat from the sheer force of the wind. The storm is raging. We have been knocked down again. We are spending the rest of the night in our wet weather gear.

Two more knockdowns before dawn. It is like being hit by a truck.

June 17

0900 (9am) The wind has changed direction, West North West, at 50 – 70 knots. It is still cyclone force. The barometer is up one point to 998. We are running under bare poles.

June 18

We ran North–East today. We are now at latitude 35.20 longitude 75.50.

During the evening the winds reached their strongest levels yet. The sound is unnerving… howling and whining. Ferocious. It blew 70–80 knots. We tried to control the boat running under bare poles but by midnight we tied the rudder amidships and went to bed fearful of knockdowns. I am understandably nervous of breaking seas at night after our recent experience.

We are still at least a month from home and any emergency assistance would take days to reach us.

June 19

Joe has described last night as the most frightening night that he has ever spent at sea. Considering that he has been at sea for 60 years and the terrible week of storms that we have endured, being thrown upside down (boat and all) in the sea at night, that is quite a statement.

1100 (11am) The barometer is 1005 and rising! At last we may have an opportunity to dry our clothing and sleeping bags.

June 20

At last the weather is improving. The Barometer is 1016, but the winds are still at 55knots. There is a Southwesterly swell with breaking crests.

1200 (noon) A clearing southerly… a high pressure system is established! Looking forward to our first night anxiety free since June 13!

Chicken Teriyaki for dinner.

The next four weeks were relatively trouble free. Having lost our radio in the roll over, we were unable to contact our families to let them know that we were ok. We were carrying an EPIRB (Emergency Position Indicating Radio Beacon), which we had not set off. We hoped that this had given them some comfort.

July 19

Our last day at sea. This voyage has been an extraordinary experience. For some reason I seem to be driven from time to time, to take on projects which push me beyond my comfort zone – past reasonable limits. This 5000–mile passage across the Indian Ocean really tested me.

I was pleased to put my sea legs on solid ground. 63 days is a long time to see nothing but water.

The demands were similar to the mountaineering expedition I undertook in 1969, the first Australian Andean Expedition – only then I was in my 20’s. Isolation, without much hope of help; similar planning in terms of food and equipment; drinking rations because you only have what you can carry; the need to endure whatever weather prevailed. Companionship – the need to rely on and support each other. Coping in a positive way with hardship and benefiting from it.

Isolation for two months is wonderful. I had time to think and take stock. When we were being knocked down and rolled upside down during two weeks of the most ferocious storms I could imagine, I faced the possibility that this could be my last adventure. Our lives were literally threatened.

I realized how fortunate I am to have a wonderful family and friends, to live in the best part of the world and enjoy a perfect lifestyle. What a tradgedy it would have been to sacrifice and bury all of that under one wall of water.

I feel fitter, healthier, stronger and more confident than before. And strangely, more relaxed.

Theodore Roosevelt said:

“Far better it is to dare mighty things, to win glorious triumphs, even though checkered by failure, than to take rank with those poor spirits who neither enjoy much nor suffer much, because they live in a grey twilight that knows neither victory nor defeat.”

I agree with him.

Client: Richard Bennett Photography