The mysterious language of pain and the fight to switch it off.

Within our bodies, we have an intricate network of nerve cells that help us to perceive the world. They’re called sensory neurons. Sensory neurons convert external stimuli from the environment into messages within the body. One of their roles is to transmit pain messages to the brain.

It is a useful process that protects us from damage (in the case of touching a hot surface), but with certain diseases, it can cause debilitating chronic pain that science is currently at a loss to treat.

The Vetter Group, lead by Dr Irina Vetter, is part of IMB’s Centre for Pain Research. They are demystifying the different pathways that contribute to pain in various disease states so that we can help the one in five Australians that live with chronic pain.

“Chronic pain costs the Australian economy around $40 billion per year and the global pain market continues to grow. It causes enormous disruption to people’s physical and mental wellbeing and their personal life. There is also a lot of stigma around pain because of the lack of understanding about its cause, and because you cannot see pain,” said Dr Vetter.

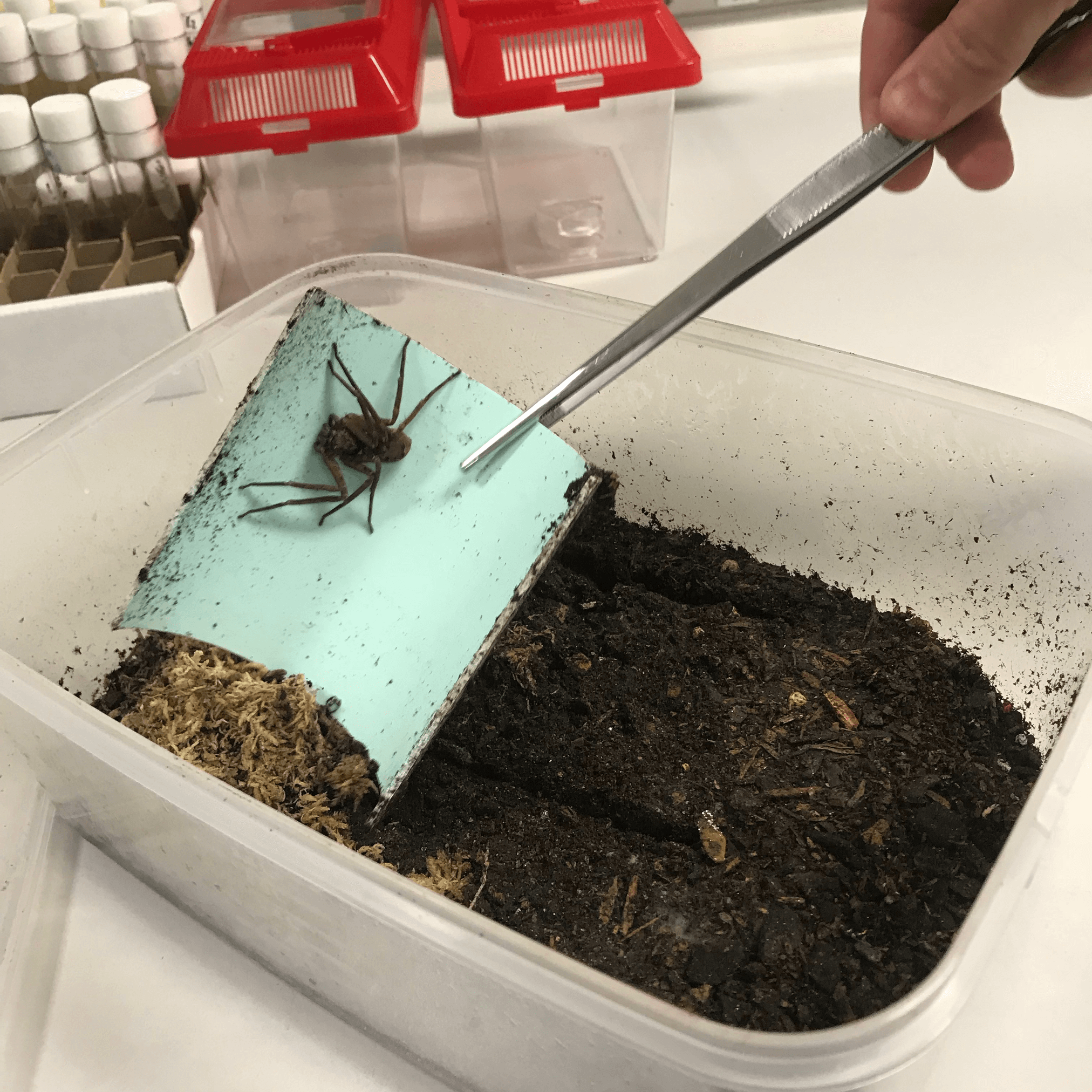

Current drugs either don’t work or have terrible side effects, like addiction. But the Vetter Group is looking to change that. Through biomedical research and pharmacology, they hope to develop better treatments for pain – targeted treatments with no adverse side effects. They are searching for answers in what might seem like a peculiar place – venoms.

“Sensory neurons transmit pain messages, and for a sting to be effective, it must be painful. So venomous animals and toxins have evolved to very specifically target sensory neurons. To treat pain, we also need to be able to target sensory neurons, so we’re examining the active components in venom and toxins to see if they can teach us how to do that.”

-683x1024.png)

A potential new pain drug discovered

The Vetter Group is currently very excited by a venom–derived compound that targets a particular protein on a nerve whose role is to signal pain.

“The protein is not involved in touch or other sensations. So this compound has exciting prospects as a pain drug. It is very selective, which means it doesn’t have any side effects, so we will take this further and hopefully make a new drug,” said Dr Vetter.

The group is confident that the drug will be effective against common types of acute pain and a rare and excruciating disease called Man on Fire Syndrome. They are also hopeful that it will be useful in a treating a wide variety of disease–related pain such as postherpetic neuralgia, diabetic neuropathy, cancer pain, and chemotherapy–induced pain. Chemotherapy induced pain for example occurs in more than 90% of patients, can force people to stop life–saving treatment, and it can be irreversible.

The group is currently looking for funding to continue their research on the compound to explore which disease related pain and acute pain the compound would be effective against.

The translation of this research into a usable drug is a long process. But the Vetter Group is also employing unique pharmacological methods to repurpose existing drugs, for more immediate translations into clinical practice.

“We have a translational capability. We always make sure that what we find in a cell has meaning in an organism. We’re well placed to deliver real outcomes.”

Dr Irina Vetter is Deputy Director of the Centre for Pain Research.